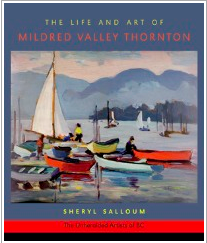

The Life and Art of Mildred Valley Thornton by Sheryl Salloum

Posted by Daniela Elza on Aug 10 2011

Mother Tongue Publishing has done it again. In this latest contribution to The Unheralded Artists of BC Series we are introduced to Mildred Valley Thornton: a painter, a poet, an advocate for first nations, for women and art.

What we love startles us awake (says Aislinn Hunter in her latest book A Peep-show with views of the interior: Paratexts). And it is here that I find the source of Mildred’s strength and passion. She loved big and she loved a lot. This passion transfers to her art, and wakes us to the existence and the possibilities of dwelling in the world, of our interconnections with it and with each other. Art “as an essential and guiding component of life” (p. 15). Art as a place to “enter into quiet communion with the aesthetic elements that exalt and elevate the race” (p. 15).

I wondered if Mildred’s journey would have been different had she not left Saskatchewan?

I wondered if her art would have been more appreciated by the establishments of the time had she not been so outspoken? Such questions tugged on me as I read.

Author Sheryl Salloum takes us on the colourful and multifaceted journey that was Mildred’s life. (I allow myself to be on a first name basis here with Mildred, since I found myself so close in sensibility, passion and love, in such kindred spirit company that using Mildred’s second name to refer to her will just introduce an unjustified and artificial distance.)

Mildred’s activism, her involvement and contribution to local and provincial art, to cultural, literary and social groups is admirable. She encouraged and helped other artists express and make a living through art. She was fascinated with first nations people, which launched her into hundreds of portrait canvases documenting faces and activities of First Nations as historic documents.

“She painted people in such places as fields, barns, and in their beds. Instead of working in a comfortable studio over a series of sittings, Mildred usually had one opportunity and a limited time to capture the likeness and character of her subjects” (p. 40). Author Sheryl Salloum highlights that by working that way Mildred broke from the portraiture tradition of studio sittings.

I was saddened to find out that our Vancouver Art Gallery has only one canvas of hers and has only displayed it about three times. Just when I was considering renewing my family membership there. I might have to ask them some questions first.

Hoping to leave a historic legacy with her art Mildred tried to keep the collection together in the hope that the government will purchase it and keep it in the province. She was so distressed by the lack of a reasonable outcome that she wrote a codicil to her will where she wanted her paintings of First Nations people to be destroyed. Thank goodness the work remained in tact.

Sheryl Salloum says in an interview: “Readers will find the art of Mildred Valley Thornton fascinating because they will discover that Emily Carr is not the only intriguing early female BC artist. Thornton was accomplished with both watercolours and oils and portraits and landscapes. The book has 100 beautifully reproduced images of her paintings as well as 18 rare and significant photographs.

Readers will also be astonished by the adventurous, confident, and passionate nature of a Canadian woman who, in the early part of the twentieth century, was ahead of her times.” I know I was taken by Mildred’s passion and unceasing struggle to build bridges and better understanding of First nations people through her art.

Hope you can pick up a copy of this or any of the other three books which cover the life and art of sculptor David Marshall, painter George Fertig, as well as The Life and Art of Frank Molnar, Jack Hardman & LeRoy Jensen.

This week at the Gala Night on Friday August 12 Mother Tongue Publishing will receive Pandora’s Collective Publishers Award for their contribution to Canadian books, for their brave and courageous undertaking to bring new and forgotten voices into the literary and art conversation.